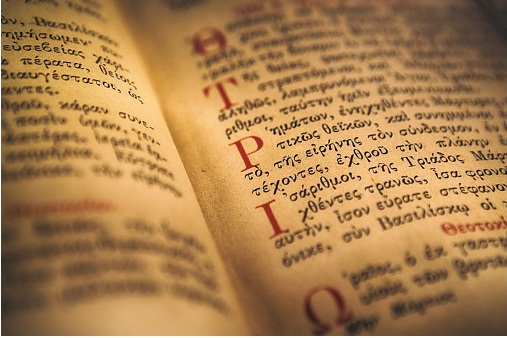

The Language of the New Testament. My studies convinced me that the books which are part of the New Testament were all written before the end of the first century in the most widely spread language of the time: Greek.

Why Greek?

During those days the Roman Empire was the leading world power, ruling over the lands around the Mediterranean Sea. But its military conquest had not been able to affect the extension of the supremacy of the Greek language and culture. Just like the fall of the British Empire did not mean the end of the diffusion of the English language, also in the ancient world neither the death of Alexander the Great, the first agent of worldwide hellenization, nor the division of his empire, nor the Roman conquest were able to remove the Greek influence. On the contrary, the Romans themselves were fascinated and seduced by the Greek world.

In the third century BC, in Egypt, under the Dynasty of the Tholomeos, the Bible began to be translated into Greek. This version of the Hebrew Scriptures began very early to be called the Septuagint, which means Seventy (abbr. LXX) because of the number of the original translators and the providential circumstances under which the Pentateuch’s Greek version was completed. Whether history or myth, the name remains to this day.

What was the type of Greek used for the Septuagint?

Just like today’s English can be distinguished in its derivations: British, American, Australian, etc… The Greek of the third century BC, being a language spoken worldwide, also by non native speakers, offered a variety of choices.

Classical Greek was the elegant, sophisticated literary language. It was used by the intellectuals, philosophers and writers. But the LXX’s translators prefered Koiné Greek, a less rhetorical, more practical, accessible, elastic, fluid form of language. More open to innovation and to the introduction of new words, it was definitely more fit to express the Hebrew religious language. The latter was characterized by a very rigid, well fixed technical terminology, fundamentally impossible to be fully translated into classical Greek and that, by consequence, needed a form of language that could be better adapted to a better expression of foreign ideas and culture.

The Septuagint is an object of very deep study up to this day. It is indeed hard to underestimate the importance of the LXX version of the Old Testament, its contribution for a better understanding of the Hebrew Scriptures, facts and terminology. It also influenced the New Testament as we examine the original language in which it was written, that is a later development of the same Koiné Greek of the LXX.

Jesus’ mandate was to spread the good news throughout the whole world.

“Go therefore and make disciples of all the nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit.” (Matthew 28:19 – NKJV)

“you shall be witnesses to Me in Jerusalem, and in all Judea and Samaria, and to the end of the earth.” (Acts 1:8 – NKJV)

The most obvious thing was that the apostles and the disciples would choose a language for the Scriptures of the Christian faith that would ensure the growth of the Church outside of the boundaries of the Jewish nation. Koiné Greek was perfect for this purpose.

Literarily speaking the New Testament – as well as the Old – is not the work of one single writer. Usually when we read the various translations, the change of the language and the presence of a translator will naturally uniform the style of the books of the Bible. But if we read the originals we will suddenly notice the different linguistic characteristics of each writer.

If we compare Mark to John, both words and style could hardly be more different. Paul writes even in a very peculiar way. He has a perfect knowledge both of Greek and Hebrew, which is quite evident in the accurate terminology that he displays to lay the foundations of the Christian doctrine.

Luke writes the introduction to his gospel in classical Greek, elegant and rhetorical in style, which made his work more popular among the sects hostile to the Jewish heritage.

All of the authors of the books of the New Testament – and I feel authorized to say, also the Holy Spirit – have given up artificial structures of literature, in order to embrace the vivid and accessible vernacular of the people.

The repercussions of this choice are amazing and we experience them on a daily basis when we read the Word of God, understand and live it.

The Greek of the New Testament is simple and clear, but by no means elementary or simplistic. It is not sophisticated for the simple reason that it is intended to communicate – not to boast knowledge and technique, but it never gives up its own identity and the characteristics. These traits, which make it a literary phenomenon of its own, are those with which almost every culture had to confront itself ever since the New Testament was written.

It is worthwhile notice that the Hebrew influence on the biblical Greek gave rise to a new religious terminology which would enrich the Greek vocabulary so that it could properly describe the truths of the Christian religion.

As far as the Greek influence on the Hebrew religion is concerned, there might be different opinions on the subject, since it is objectively a far more complicated matter. Personally, I believe that though the Jews might recognize the value of the Greek language, their religious identity was too strong to be contaminated with Hellenistic practice and beliefs. The strong influence of Antiocus Epiphanes or other rulers who tried to impose paganism, rituals and thought, simply led some to deny their Jewish heritage by accepting the Hellenic philosophy. In a few words, orthodox Judaism, after the Babylonian captivity of the sixth century BC, was not inclined to compromise with any foreign culture as time and circumstances have abundantly left evidence in history.

Going back to our main topic, the language of the LXX and of the New Testament, was simple, innovative; clear, live and stimulating.

Let’s see some examples in detail.

The Greek word “agape” (in the original Greek alphabet: αγαπη), which is famous also to many who have nothing to do with biblical Greek, is a peculiar word from the LXX and the New Testament. It is not found in classical Greek. The King James Version translates it “Charity”, which corresponds to modern “love” used by more up to date versions.

Another famous Greek word is “zoe” (ζωη) which means “life”. We find it used in particular in the gospel of John, where such a colloquial word has been enriched to the extent of reinventing it altogether, keeping only the original form of it, but to express and communicate wonderful new meanings.

In its original meaning, zoe has nothing of the deep spiritual meanings that the apostle attaches to it.

There is one word which is really worth not only mentioning but also considering.

We find it in the book of Revelation: “pantokrator” (παντοκράτωρ), which means “Almighty”.

“I am the Alpha and the Omega,” says the Lord God, “He who is and He who was and He who is to come, The Almighty.” (Revelation 1:8)

Outside of the book of Revelation we find this same term in 2 Corinthians 6:18.

John took the word Pantokrator from the LXX translation where it thus rendered the Hebrew expression which in our Bibles is usually translated as “Jehovah of hosts” (ASV) or “Lord of Hosts” (KJV). In Nahum 2:13 the LXX reads Kyrios Pantokrator (κύριος παντοκράτωρ), literally: “Lord Almighty“.

Why did the LXX translators choose to do so?

The Greek Pantokrator was used to translate the Hebrew term Sebaoth (צבאות) also in ancient books of the Bible. It literally reviews the original Hebrew word (Jehovah of Hosts) giving it a more universal meaning, becoming its Greek evolution, expressing the absolute sovereignty of God over all creation and every creature.

The Greek term itself might even have been created to translate the Hebrew here. This would explain why some other Old Testament books of the LXX do not translate the word but simply transliterate it into the Greek alphabet: κύριος σαβαωθ, (Isaiah 1:9), which has been translated in English as: “Jehovah of Hosts” (ASV).

There is another expression used by John in the same context which is indeed worth mentioning. Addressing God as “the Lord God, who is and who was and who is to come” I believe he gave the equivalent in the Greek language of the Hebrew יהוה as much as “Pantokrator” translates the Hebrew צבאות (Sabaoth).

John knew the Tetragram, the Name of God revealed to Moses, YHVH (in Hebrew alphabet יהוה), but instead of transliterating it from the Hebrew, applying a similar process that brought to the birth of the word “Almighty”, he thinks it better to try to simply communicate the immediate meaning of that Name in Hebrew.

The four Hebrew consonants are vocalized in the Masoretic text as follows: יְהוָֹה If we simply add the vowels’ symbols to the consonants, we’ll read in our alphabet the familiar YeHoVaH.

Asher Intrater is a Messianic Jew. He writes in his book “Who ate with Abraham?” that the sequence of the three vowels “e” (sh’va), “o” (holom), “a” (patach), indicate the root of the future, present and past tense.

We might even conclude that the phrase found in Revelation 1:8 was an attempt to render the Jewish name of God (צבאות יהוה) “Adonai Sebaoth” following the principles of the LXX translators, expanding the narrow Hebrew expression Sebaoth, giving it a meaning, a religious meaning, for the Greek speaking world when interpreted it as “Pantokrator”, which is in English “Almighty”.

So the national צבאות יהוה (Adonai Sebaoth) – “Jehovah of Hosts” – becomes the universal “Κύριος ὁ Θεός, ὁ ὢν καὶ ὁ ἦν καὶ ὁ ἐρχόμενος, ὁ παντοκράτωρ” which the ASV renders in English: “Lord God, who is and who was and who is to come, the Almighty.”

Another very important Greek word is Logos (Λόγος) used by John in his gospel, in order to fully explain the relationship of Jesus with the Father and the Creation, before becoming a man. Logos is usually translated as “Word”.

“In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.” (John 1:1)

Logos is found in Greek philosophy long before it was used by John. This must not entitle us to believe that the apostle was looking outside of the Hebrew world in order to find ideas that could express the eternal state of the Savior, but a Greek terminology was simply borrowed in order to express a deeply Semitic concept.

The Greek fathers of the Church, such as Justin Martyr (second century), took the chance of this familiarity of the Greek speaking world with the idea and term of Logos to preach Jesus in a way that might be familiar to the non-Jewish people.

Nothing happens by chance – every believer must be deeply convinced of this.

The Hebrew language was born and raised along with the Faith in the Personal God of the people who spoke it: that is why it perfectly conveys the facts and ideas of the Jewish religion.

The Greek language had reached quite a large diffusion and the necessary maturity when it came in contact with the Old Testament: in the right hands it could express any concept, abstract or practical. It became the language of the Septuagint and later that of the New Testament, the perfect means through which the faith in Jesus might be shared with people virtually everywhere.

A universal language for a universal message

There are some who try to recover the Jewish heritage of our faith by simply recovering in our Bibles the Hebrew original names of God (Jehovah or Yahweh, Elohim, etc.) of Jesus and even the apostles.

With due respect, it is not necessary to go back to Hebrew names or terminology in order to believe to be more faithful to the pure original doctrine of Jesus and the apostles.

Also because, taking a closer look at the language of the New Testament, we understand that the attitude of the early Church pointed to a totally different direction.

I am by no means trying to underestimate the importance of the study of the Jewish linguistic and cultural background in order to develop a better understanding of the New Testament, of the teachings of Jesus and of the Christian doctrine and practice. But at the same time, it is vital to understand that we must not neglect the universal linguistic heritage embraced in the New Testament when choosing the Greek language to convey the message of the new faith.

Let us consider a practical example, Isaiah 7:14.

“Therefore the Lord Himself shall give you a sign: behold, the young woman shall conceive, and bear a son, and shall call his name Immanuel.” (Isa 7:14 Jewish Publication Society – 1917)

“Therefore Adonai himself will give you people a sign: the young woman will become pregnant, bear a son and name him ‘Immanu El [God is with us].” (The Complete Jewish Bible – ed. 1998)

The above Jewish translations render the Hebrew word העלמה (transliterated in our alphabet as: ha-almah) as “young woman.”

Matthew so quotes this passage in the New Testament: “So all this was done that it might be fulfilled which was spoken by the Lord through the prophet, saying: “Behold, the virgin shall be with child, and bear a Son, and they shall call His name Immanuel,” which is translated, “God with us.” (Matthew 1:22-23 – NKJ)

The Greek original of Matthew renders the Hebrew word העלמה (ha-almah) of Isaiah 7:14 with “ἡ παρθένος” (he parténos), a word which inequivocably refers to a “virgin”.

If we put too much stress on the original Hebrew of Isaiah 7:14 we will miss the fulfillment of the virgin birth of Jesus of this precious Old Testament prophecy. Because the Hebrew word meant also “young woman” but the important detail is that this “young woman” implies a “virgin”. The Septuagint, the Greek translation much older than the New Testament sanctions the view of Matthew. It renders Isaiah 7:14: “ἰδοὺ ἡ παρθένος ἐν γαστρὶ ἕξει”.

The contribution of the Greek language in the correct understanding of a Hebrew original is here undeniable.

Monotheism was exclusive of the Jewish nation. Hebrew was the language that described the Jewish faith, its beliefs, God, etc. But in the New Testament the Gospel is universal and it takes a universal language to be able to express the new Faith to new believers, most of Greek cultural background, not linked by any national bond or birthright, but by love..

Paul tore down the walls between Jewish and non-Jewish Christianity. His missionary activity was all directed to the people living outside of Israel, both physically and ethnically.

“For I speak to you Gentiles; inasmuch as I am an apostle to the Gentiles, I magnify my ministry.” (Romans 11:13 – NKJ)

A very important step toward the universal message of the Gospel is substituting the ineffable Old Testament Name of God with the accessible and universal Kyrios, Lord.

This is evident in a very important passage of the epistles of Paul.

“ … that if you confess with your mouth the Lord Jesus and believe in your heart that God has raised Him from the dead, you will be saved.For with the heart one believes unto righteousness, and with the mouth confession is made unto salvation. For the Scripture says, “Whoever believes on Him will not be put to shame.” For there is no distinction between Jew and Greek, for the same Lord over all is rich to all who call upon Him. For “whoever calls on the name of the LORD shall be saved.” (Romans 10:9-13 – NKJV)

If Paul had inserted here the Tetragrammaton, he would have openly contradicted the basic value of his statement, since among the “whoever” he included even those who could not pronounce or had any knowledge at all of the Hebrew HaShem (The Name) of God יהוה. On the contrary, he speaks of God as Kyrios, so that virtually everyone and everywhere knew what he was talking about and could be saved by calling upon the name of the Lord. The last quotation in Romans 10:9-13 is an Old Testament passage which included the Tetragrammaton, יהוה!

Paul’s quotation recalls the Septuagint Greek translation.

πᾶς γὰρ ὃς ἂν ἐπικαλέσηται τὸ ὄνομα Κυρίου σωθήσεται (New Testament)

καὶ ἔσται πᾶς, ὃς ἂν ἐπικαλέσηται τὸ ὄνομα κυρίου, σωθήσεται (Septuagint)

The Greek text of Joel 2:32 available for Paul must have been the same as the one we consult today.

In the New Testament the national God who revealed Himself to Moses a יהוה, becomes Lord of every man (Kyrios) calling upon His name.

The national bond of God with Israel is now substituted by relationship, which starts when anyone, anywhere open their heart to God. “But as many as received him, to them gave he the right to become children of God, even to them that believe on his name: who were born, not of blood, nor of the will of the flesh, nor of the will of man, but of God.” (John 1:12-13 – ASV)

New wine into new wineskins

We saw how the Greek of the New Testament took the Hebrew terminology. This guaranteed that continuity which was desirable, between the Old and the New Testaments.

At the same time, the circumstances were new, the language was new and the new faith had to shed light on many details of the Revelation now become more evident because of the incarnation of the Son of God.

Philo was a Jewish “philosopher” who live in Alexandria, Egypt, between 50 BC and 50 AD. His teachings on the logos, the word (see John 1:1) closely resembles that of Paul and of John and it must have been relying on the Jewish thought of the time as the Targumin confirm.

But the apostles move forward, they report something that the official Jewish religion failed to see. They openly declare that the logos was manifested in the flesh, became a man: Jesus of Nazareth.

The epistle to the Colossians introduces a terminology which has no parallel in Hebrew.

“ὅτι ἐν αὐτῷ εὐδόκησε πᾶν τὸ πλήρωμα κατοικῆσαι.” (Colossians 1:19).

“For it pleased the Father that in Him all the fullness should dwell.” (NKJV)

The word πλήρωμα (pleroma), “fullness”, has here specific traits. It is a technical word which includes what Paul himself will clarify later in the same epistle. No trace of this terminology is found in the New Testament: the new faith needed new words!

“ … ὅτι ἐν αὐτῷ κατοικεῖ πᾶν τὸ πλήρωμα τῆς θεότητος σωματικῶς,” (Colossians 2:9).

“for in Him dwells all the fullness of the Godhead bodily.”

Paul is using a language which is so accurate! His terminolgy leaves no room for any doubt whatsoever on the fullness of the Deity of Jesus. If others today think otherwise, the apostle Paul has no fault at all.

“τὸ πλήρωμα” is the sum of all the divine attributes and qualities of God.

“θεότητος” is Godhead, a word that you will not find anywhere else in the New Testament.

Such terminology was never found in the Old Testament.

Another wonderful quality of our Lord Jesus Christ is

described by the word εἰκὼν, image, which Paul uses in Colossians 1:15: “ὅς ἐστιν εἰκὼν τοῦ Θεοῦ τοῦ ἀοράτου.”

In English: “He is the image of the invisible God.”

Again, this statement has no parallel in the Hebrew Scriptures.

The beginning of the epistle to the Hebrews has such a wonderful Christological terminology! It is almost impossible to exactly translate it into English.

“ὃς ὢν ἀπαύγασμα τῆς δόξης καὶ χαρακτὴρ τῆς ὑποστάσεως αὐτοῦ”. Which the New King James renders: “… who being the brightness of His glory and the express image of His person…”

Both “εἰκὼν” and χαρακτὴρ express very deep Christological concepts and could be introduced in the Christian language, thanks to the high speculative level of the Greek language. Similar words are not referred to the Messiah in the Old Testament. Greek helped the holy men of God to shape the doctrine of the new faith in Jesus.

John wrote in his Gospel using a terminology that shaped the Christology of the Church. The prologue recalls the solemnity of the Genesis account of creation.

“In the beginning was the Word (Gr. logos), and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.” (John 1:1).

Philo wrote about the logos, the Word, too. He does it from a Jewish perspective and very probably influenced by the Jewish speculations of the time on the matter. In his wonderful work “On The Creation”, also known as “De Opificio Mundi”. There Philo speaks of the “θείῳ λόγῳ”, a phrase that C. D. Yonge translates as “Divine Reason”, but that we can also interpreta s “Divine Word”, since logos in Greek can mean both “reason” and “word”.

John says more than Philo. The apostle connects to his Jewish roots, because their interpretation was not entirely wrong. But adds: “Θεὸς ἦν ὁ Λόγος”, “The Word is God”.

John knows something that Philo did not know and could not know. The apostle’s knowledge of the Word was personal and direct, not simply speculative like Philo’s.

“And the Word became flesh and dwelt among us, and we beheld His glory, the glory as of the only begotten of the Father, full of grace and truth.” (John 1:14 – NKJV)

The Jewish commentators had altrady spoken of the manifestations of God through what or who they called “Memra”, in Aramaic or “Davar” in Hebrew. When the New Testament (as well as Philo) speaks of a logos of God, revealed to mankind in the person of Jesus, it gives a universal message that has a meaning both for the Jewish people and for the Gentiles, since a common Greek term becomes the perfect means to express a deeply Hebrew idea.

The apostles themselves, through the guidance of the Holy Spirit, were the first to deliver the message of the Gospel to the non-Jewish. They did so, speaking of the wonders of God in the only universal language of their time: Greek.

The God of Moses was remembered in Israel as the one who set the people free from the slavery in Egypt. But to the Gentiles He was now proclaimed as the Almighty God, Creator of all things and above all the Father of the Lord Jesus Christ, whom He had sent to save mankind – those who received Him in their hearts as Lord and Savior.

The Hebrew heritage of our faith is quite intriguing. But we cannot simply stop at the contemplation of the old covenant. The apostles moved on. They promoted the use of a language which made their message universally understood: being accessible is far more important than the purity so cherished even then by certain Jewish circles. Not the words themselves are sacred, but the message they deliver.

HaShem, il Nome, יהוה, is not sacred in itself, but Holy is the God that we address by that name. If יהוה cannot even be pronounced, the idea which it recalls is too distant from the Gospel, Kyrios, Lors, becomes no less sacred if Holy is the God we are calling upon.

If יהוה had freed Israel from Egypt and given the Law to the people, now Godi s the Father of our Lord and Savior, Jesus Christ.

In the light of what has been said so far, I am sure the student of the Bible will agree on how important it is to seriously study the New Testament Koinè Greek language in oder to better understand “the faith which was once for all delivered to the saints.” (Jude v.3)